Apparently, if you want optimal choices, you have to buy toddler halloween costumes in July. Not knowing this, I went at the end of September and thought I was doing good. Instead, I found only two left in my daughter's size: An adorable dog and a skeleton.

Although I couldn't pinpoint why, I was disturbed by the notion of putting my 17-month old in a skeleton costume. So I made an easy choice and got the dog.

A few weeks later, we found ourselves at Boo at the Zoo. As part of the zoo's halloween decorations, they had skeletons displayed in the center of the carousel.

As we rode the carousel, I found myself unable to look at the skeletons. About half way through our ride, my husband leaned over to me and commented how uncomfortable he felt around the skeletons after our time in Rwanda.

As soon as he said that, I thought, “That's it! That's why I was so uncomfortable with the idea of a skeleton costume! That's why I can't look at the skeletons here.”

You see, we've seen skeletons in real life.

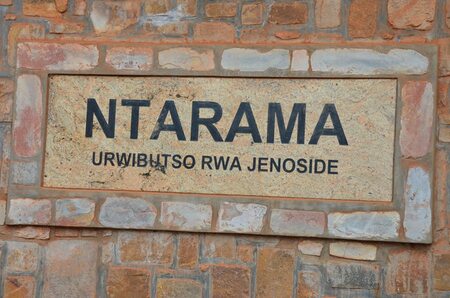

We've been to the genocide memorials in Rwanda – not just to the somewhat sanitized memorial in Kigali - but to the church memorials. The ones where you walk into a sanctuary, and 22 years later, still smell death.

In those church memorials, you see the clothes of the people who fled there, seeking sanctuary, as they had done during previous, smaller genocides. Only this time, the churches offered no safety.

Grenades were hurled into the sanctuary. Guns were fired at the men, women, and children who sat there. You can still see the bullet and grenade holes in the sanctuary walls... They make for a strange juxtaposition with the baptismal font that still stands in the front of the sanctuary.

At that memorial, you also walk into an underground crypt.

There, you see skeletons.

Not the kind we use to decorate for Halloween, but real-life skeletons.

Skeletons that used to support living, breathing people until they were brutally murdered during the 1994 genocide.

Their skeletons tell the stories of their horrific deaths. You can see skulls that were bashed in from beatings; Others that were severed by machetes; Some bodies that were impaled.

I've taken a deep breath before then walking in and out of another church memorial. In this one, you walk through Sunday school rooms with walls stained with blood from hurling babies at them in order to kill them.

I've walked hand in hand with high school students through another sanctuary, this one filled with the skeletons of those who were killed there.

I've walked those church memorials in tears, horrified by what one people group can do to another as the world stands by and watches.

I've stood outside those church memorials with high school teens, helping them to catch their breath, reassuring them it's okay to throw up if they need to.

I've gotten back into a bus and sat in silence with normally boisterous missions' teams whose experience at the memorials has left them speechless.

I've processed those memorials with missions' teams, helping them to understand why we go to them to learn and remember; why we hope that such memorials will actually make this a world in which genocide stops happening.

Having seen the skeletons of real people, I can't bring myself to dress my daughter in such a costume for Halloween; I don't think I'll ever display a toy skeleton on my front porch as a Halloween decoration.

Such things might seem amusing here.

But there are so many places around the world where skeletons aren't merely decorations.

They're remembrances of real-life death, horror, and grief.